The Nile River provides a fabulous journey through splendid desert scenery, an ancient civilisation and the hubbub of contemporary Egypt, writes Brian Johnston.

Most of Egypt is silent desert, blazing sun and rock red as the dawn of time. Then suddenly the Nile River flows, a great pumping artery of water in the barrenness, and on its banks erupts a whole civilisation: ancient temples and glass skyscrapers, fields of rice and feathery date palms, roads, railways and villages of mud brick. This gift in the wilderness is Egypt, with 90 per cent of the country’s population packed into just three per cent of its landmass.

For thousands of years the river has been a lifeline – and a lure to travellers. The Nile offers temples and tombs from a dazzling civilisation that owes everything to the river’s sluggish majesty. The Nile is both the symbol of ancient Egyptian culture and the heartbeat of a modern nation, and you’ll never tire of its changing river-scapes. Travel its banks by train, float along it on a cruise ship, walk its promenades, and the whole of Egypt unfolds.

The most important stretch of the Nile flows between the cities of Aswan and Luxor in Upper Egypt, where the river is lined with the world’s greatest collection of ancient palaces and temples. Luxor is the ancient capital of Thebes, and the Nile River neatly divides its sights in two: the former capital and its grand temples on the east bank, pharaohs’ tombs and mortuary temples on the west bank. The contrast is startling. The west bank is imbued with a brooding calm, the desert sands punctuated with worn-down statues and silent gaping tombs, while the east bank’s modern town is full of hubbub, street markets and hotels. The riverside promenade known as the Corniche gives you a grandstand view of the Nile and its sailboats and river-cruise ships. Along the promenade’s length, horse-drawn carriages clip-clop past, old men perambulate and street-smart hustlers sell felucca tours and statuettes of cats and pharaohs. Luxor is the departure point for a Nile cruise to Aswan, which usually takes three days. Ships sail between the red, rocky hills of the desert. Villages and neat farmland slide by, allowing you a glimpse of rural Egypt you mightn’t otherwise see. The days fizzle out in sunsets that turn the surrounding desert orange, providing the beautiful moments that travel is all about.

Along the way, grandiose temples loom. At Edfu, the Temple of Horus is one of Egypt’s best preserved ancient buildings, guarded by brooding granite falcon statues and covered inside with friezes and hieroglyphics. Further south, another grand temple stands on a bluff above the river at Kom Ombo. Wall inscriptions depict the crocodile-headed god Sobek, and you can inspect the remains of macabre mummified crocodiles in side buildings, a reminder of how the Nile permeated every aspect of ancient Egyptian life. Other gods have the heads of hippos and ibis, and the great sun god Ra was rowed across the heavens in a boat.

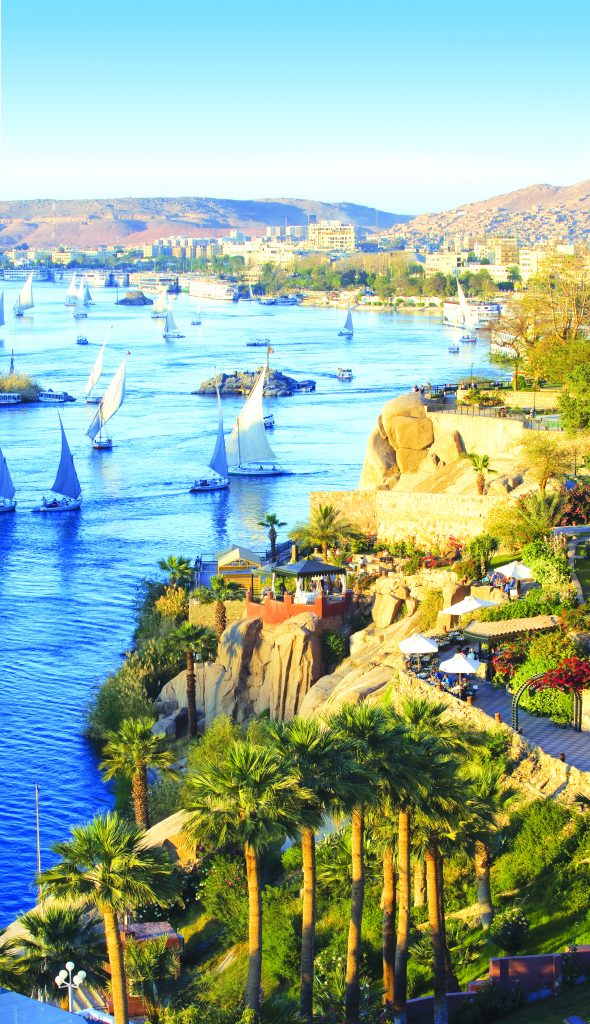

Whether you travel by road or ship, Aswan is usually the last stop on the river, which narrows here between sand hills and giant granite boulders, marking the southernmost point of the navigable Nile. Cataracts once flowed above the town, now tamed by the Aswan Dam. Aswan’s setting is one of the loveliest in Egypt. Climb into a felucca – a sailing boat scarcely changed since the time of the pharaohs – and explore the sluggish river’s scattered islands. The Island of Plants has dusty botanical gardens and brilliant views over the sand dunes and tombs of the west bank. Elephantine Island, named because its granite boulders resemble bathing elephants, is home to three Nubian villages.

You might also want to inspect the nilometre, a series of 90 steps complete with pharaonic markings and inscriptions. In ancient times the nilometre was used to calculate the river’s rise between June and September when monsoon rains washed down from Ethiopia. The ancient Egyptian calendar was divided into three based on the river’s cycles: akhet or flooding season, peret or growing season, and shemu or harvest season. When the river and fields were flooded farmers were unable to work, leaving a plentiful supply of labour for massive building projects. Even the glorious temples that line its banks are the result of the Nile’s bounty, without which all of Egyptian civilisation would never have happened.

Aswan was known as Swenet in ancient times. The name simply meant ‘trade’, and trade flowed down the Nile to the Mediterranean in the one direction, and by caravans of camels to Nubia and the rest of Africa in the other. The ruins of Swenet are somewhat uninspiring, and you’ll get a better flavour of life in ancient times by heading into the town’s street markets a few blocks behind the river. Nubians in long blue robes barter with Bedouin traders and Egyptian middlemen, squabbling over glasses of tea as spices, salted fish, cotton and carpets are sold. It’s the Nile alive with trade and chatter as it has been for thousands of years, and eternally fascinating.